Denied for Your Faith? The Reality of Religious Discrimination

For many, faith is not merely a weekend activity; it is the compass that guides daily life, influencing diet, dress, and ethical decisions. Yet, in the modern workplace, employees are often forced to make an impossible choice between their career and their conscience. Despite robust legal protections at both the state and federal levels, religious discrimination remains a pervasive issue in American offices, factories, and retail floors.

No worker should have to hide their identity or compromise their sincerely held beliefs to keep a paycheck. Understanding the nuances of the law—and the obligations of employers—is the first step toward combating unlawful treatment. Whether you are an employee seeking to understand your rights or a manager aiming to foster an inclusive environment, recognizing the signs of discrimination is essential for maintaining a just workplace.

Defining Religious Discrimination

At its core, religious discrimination involves treating a person (an applicant or employee) unfavorably because of their religious beliefs. The law protects not only people who belong to traditional, organized religions, such as Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam, and Judaism, but also others who have sincerely held religious, ethical, or moral beliefs.

Under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and California’s Fair Employment and Housing Act (FEHA), protection extends beyond belief to include religious observance and practice. Crucially, the law also protects those who have no religious beliefs, shielding atheists and agnostics from forced participation in religious activities or discrimination based on their lack of faith.

Discrimination can manifest in various employment decisions, including hiring, firing, pay, job assignments, promotions, layoffs, training, and fringe benefits. It can also appear in the form of harassment—such as offensive remarks about a person’s religious beliefs or practices—that is so frequent or severe that it creates a hostile work environment.

What Discrimination Looks Like in Practice

Religious discrimination is often subtle, but it can also be overt. It frequently arises when workplace rules collide with religious obligations. Here are several scenarios that may constitute unlawful conduct:

- Refusal to Hire: An employer refuses to hire a qualified Jewish applicant because they disclose that they cannot work on Saturdays due to Sabbath observance.

- Scheduling Conflicts: An employee is fired for missing work to attend a significant religious service, even after providing ample notice, while employees taking time off for secular reasons are accommodated.

- Dress Code Violations: A company enforces a strict “no headwear” policy that disproportionately impacts Muslim women who wear hijabs or Sikh men who wear turbans, without offering a valid safety justification.

- Harassment: A supervisor or colleague persistently mocks an employee’s religious garments, prayer habits, or dietary restrictions, isolating the employee from the team.

- Forced Work: A manager demands that an employee work on their Sabbath, ignoring the fact that other qualified employees were willing to swap shifts.

Employer Obligations: The Duty to Accommodate

The law requires more than just “not discriminating.” Employers have an affirmative duty to reasonably accommodate employees’ religious beliefs or practices, unless doing so would cause an “undue hardship” on the operation of the business.

Common accommodations include flexible scheduling, voluntary shift substitutions or swaps, job reassignments, and modifications to workplace policies or dress codes.

The Shift in “Undue Hardship”

For decades, employers could deny accommodations by proving that the request imposed more than a “de minimis”—or trifling—cost. This low bar allowed companies to reject requests for Sabbath observance or prayer breaks easily.

However, the legal landscape shifted dramatically with the Supreme Court’s 2023 decision in Groff v. USPS. The Court ruled unanimously in favor of Gerald Groff, an evangelical Christian postal carrier who refused to work Sundays. The Justices clarified that “undue hardship” must mean substantial increased costs in relation to the conduct of the employer’s particular business.

This decision significantly strengthens protections for employees. Employers can no longer deny an accommodation simply because it is inconvenient or causes minor administrative annoyance; they must demonstrate that the accommodation would substantially burden the business.

Recent Legal Battles and Settlements

Recent high-profile cases illustrate that the courts and government agencies are taking a firm stance against religious discrimination. These cases, while the parties were not represented by Helmer Friedman LLP, provide important precedents and show the real-world impact of successful advocacy.

Mavis Tire Supply LLC

In late 2025, Mavis Tire Supply LLC agreed to pay over $303,000 to settle an EEOC lawsuit. The case involved a Jewish applicant who applied for a management position. During the interview, he disclosed that his observance of the Sabbath would prevent him from working Friday evenings and Saturdays.

Rather than discussing accommodation, the company offered him a lower-paying technician role, claiming it offered better flexibility. When he reiterated his schedule restrictions, they rescinded the offer entirely. The settlement highlighted that employers cannot steer applicants away from leadership roles simply to avoid granting religious accommodations.

Lisa Domski v. Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan

In a landmark verdict regarding vaccine mandates, a federal jury awarded $12.7 million to Lisa Domski, a former IT specialist at Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan. Domski, a devout Catholic, requested a religious exemption from the company’s COVID-19 vaccine mandate, citing her objection to vaccines developed using fetal cell lines.

Despite working 100% remotely with no in-person contact, her request was denied, and she was terminated. The jury found that the company failed to accommodate her sincerely held beliefs. The massive award, which included $10 million in punitive damages, sends a clear message: employers cannot dismiss religious objections as insincere simply because they disagree with the employee’s theological interpretation.

Practical Steps for Employees

If you believe you are facing religious discrimination or have been denied a reasonable accommodation, taking immediate, organized action is vital to protecting your rights.

- Document Everything: Keep a detailed record of all incidents. Note dates, times, locations, witnesses, and the specific comments or actions taken. If you requested an accommodation, keep copies of all written requests and the employer’s responses.

- Review Company Policy: Check your employee handbook for policies regarding discrimination and accommodation. Follow the internal procedures for reporting grievances.

- Report the Incident: Formally report the discrimination or denial of accommodation to your Human Resources department or a manager. doing this in writing creates a paper trail proving the employer was on notice.

- Consult a Legal Professional: Employment law is complex and involves strict statutes of limitations. Consulting with an attorney who specializes in employment discrimination can help you navigate the EEOC complaint process or potential litigation.

Best Practices for Employers

To avoid litigation and foster a respectful work environment, employers should proactively review their policies in light of recent Supreme Court rulings.

- Update Policies: Ensure the handbook explicitly prohibits religious discrimination and outlines a straightforward procedure for requesting accommodations.

- Train Management: Managers are often the first point of contact for accommodation requests. They must be trained to recognize these requests and understand that “inconvenience” is not a valid reason for denial.

- Engage in an Interactive Process: When an employee requests an accommodation, engage in a dialogue to understand their needs and explore potential solutions.

- Assess “Undue Hardship” Carefully: Before denying a request, conduct a factual analysis. Will this truly cause substantial cost or disruption? If the answer is no, the accommodation should likely be granted.

Protecting Religious Freedom at Work

A workplace should be a space of professional contribution, not a battleground for personal identity. The freedom to practice one’s religion—or to practice no religion at all—is a fundamental right that does not evaporate when an employee clocks in.

As evidenced by the Groff decision and recent jury verdicts, the legal system is increasingly protective of these rights. Both employers and employees have a role to play in ensuring that the workplace remains diverse, inclusive, and compliant with the law.

Resources for Further Information

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC): Religious Discrimination Information

- California Civil Rights Department (formerly DFEH): Employment Discrimination

- Helmer Friedman LLP: Religious Discrimination Lawyers

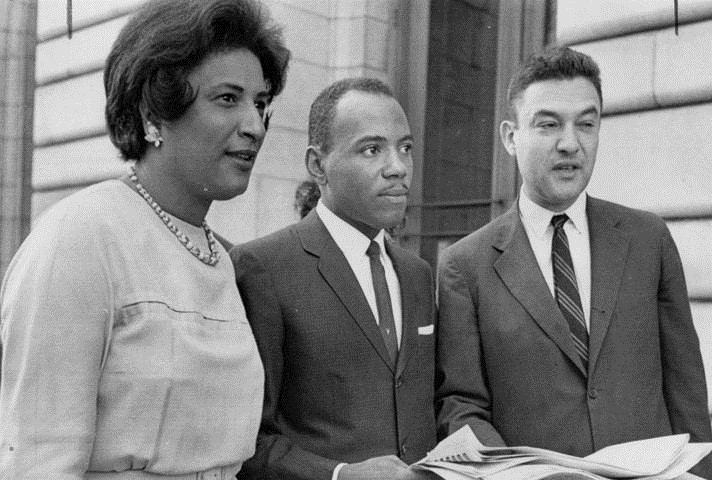

Constance Baker Motley was not only the first Black woman to argue before the Supreme Court (winning an astonishing nine of 10 cases), but she was also the first black woman to be appointed to the federal judiciary – President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed her to the Southern District of New York.

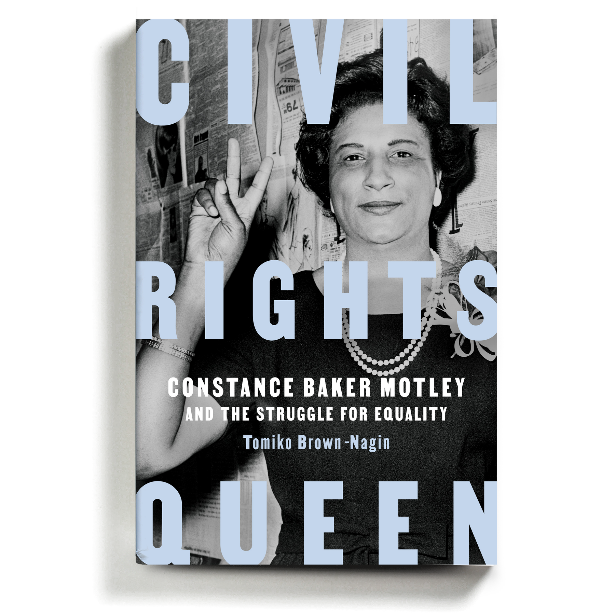

Constance Baker Motley was not only the first Black woman to argue before the Supreme Court (winning an astonishing nine of 10 cases), but she was also the first black woman to be appointed to the federal judiciary – President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed her to the Southern District of New York. In her terrific new book on Motley’s life and legacy – called “

In her terrific new book on Motley’s life and legacy – called “ On November 8, 2016, the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral argument in a case Helmer Friedman LLP successfully convinced the high court to hear. The case — Lightfoot v. Fannie Mae, Cendant Mortgage Corporation case (14-1055) — concerns whether individual homeowners who have been wrongly or fraudulently foreclosed upon by Fannie Mae have the right to sue the mortgage giant in the state courts.

On November 8, 2016, the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral argument in a case Helmer Friedman LLP successfully convinced the high court to hear. The case — Lightfoot v. Fannie Mae, Cendant Mortgage Corporation case (14-1055) — concerns whether individual homeowners who have been wrongly or fraudulently foreclosed upon by Fannie Mae have the right to sue the mortgage giant in the state courts.