In Green v. Brennan, 2016 WL 2945236 (U.S. May 23, 2016), the U.S. Supreme Court considered when the clock starts to run on a constructive discharge claim. Before discussing the Supreme Court’s decision, a little background information is in order.

Generally, employees only have limited amounts of time to bring their employment-related claims against their employers. How much time is determined by various laws called “statutes of limitation.” For example, in California, employees have one year to file a complaint of discrimination with the California Department of Fair Employment and Housing (“DFEH”). Then, employees have an additional year from the date of the DFEH’s Right-To-Sue Letter to file a lawsuit in court.

Under California state law, the statutes of limitation on a wrongful termination claim begin to run on actual termination date, rather than the date when employer informs the employee that discharge was inevitable. Romano v. Rockwell Internat., Inc., 14 Cal. 4th 479 (1996). Under federal law, the statutes of limitation begin to run when the employer notifies the employee that his or her employment will be ending. Delaware State Coll. v. Ricks, 449 U.S. 250, 259, 101 S. Ct. 498, 504 (1980).

But, when does the clock begin to run on a constructive discharge claim (a claim that the employer forced the employee to resign)? Say that on November 1st the employee gives her employer two weeks notice that she will be resigning on November 15th. Do the statutes of limitations begin to run on November 1st or November 15th? In Green v. Brennan, 2016 WL 2945236 (U.S. May 23, 2016), the U.S. Supreme Court examined this very issue. The Supreme Court concluded that the statutes begin to run on the date the employee gives notice of his or her intent to resign (rather than his or her last day of employment).

Green v. Brennan involved a former U.S. Postal Service Employee, Marvin Green, who claimed that he was discriminated against on the basis of his race (African-American). Green worked for the Postal Service for nearly 35 years. Green complained that he was denied a promotion because of his race. Not surprisingly, following his complaint, his relations with his supervisors crumbled. Relations hit a nadir on December 11, 2009, when two of Green’s supervisors accused him of intentionally delaying the mail—a criminal offense. On December 16, 2009, Green and the Postal Service signed an agreement whereby the Postal Service promised not to pursue criminal charges in exchange for Green’s promise to leave his post. The agreement gave Green a choice: effective March 31, 2010, he could either retire or report for duty in another location at a considerably lower salary. Green chose to retire. He submitted his resignation to the Postal Service on February 9, 2010, effective March 31.

Eventually, Green contacted an Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO) counselor to report an unlawful constructive discharge. He contended that his supervisors had threatened criminal charges and negotiated the resulting agreement in retaliation for his original complaint. He alleged that the choice he had been given effectively forced his resignation in violation of Title VII.

Subsequently, Green filed suit in the Federal District Court for the District of Colorado, alleging, inter alia, that the Postal Service constructively discharged him. The Postal Service moved for summary judgment, arguing that Green had failed to make timely contact with an EEO counselor within 45 days of the “matter alleged to be discriminatory,” as required by 29 CFR § 1614.105(a)(1). The District Court granted the Postal Service’s motion for summary judgment. The Tenth Circuit affirmed holding that Green’s claim was time-barred because the date Green signed the settlement agreement was the Postal Service’s last discriminatory act triggering the filing deadline that Green failed to meet.

In a 7-1 decision, the Supreme Court held the time period for filing a constructive discharge claim “begins running only after the employee resigns.” The Court explained that this means the clock begins to run when the employee gives definite “notice” of his or her resignation, not the date the resignation is effective. In other words, if an employee gives two weeks notice, the clock starts to run on the date of the notice, not two weeks later on the employee’s last day of work.

Employees considering resignation due to intolerable working conditions should consult with employment counsel before submitting their resignation. The courts have made it very difficult for employees to successfully bring a constructive discharge claim. Employment counsel can help employees properly place their employers on notice as to the intolerable working conditions.

Like this:

Like Loading...

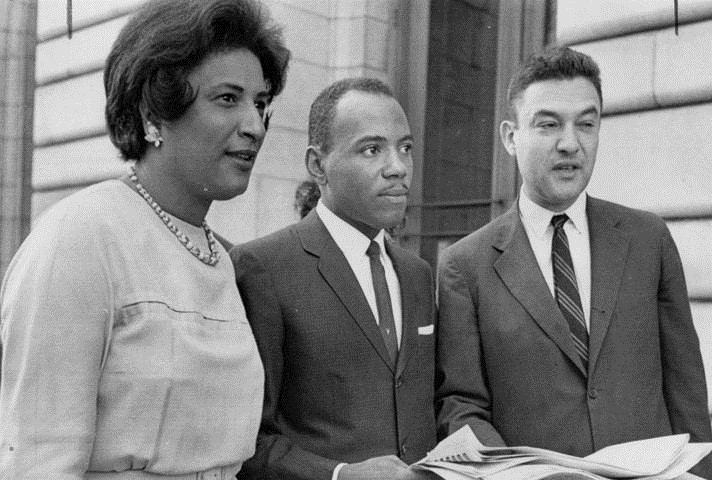

Constance Baker Motley was not only the first Black woman to argue before the Supreme Court (winning an astonishing nine of 10 cases), but she was also the first black woman to be appointed to the federal judiciary – President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed her to the Southern District of New York.

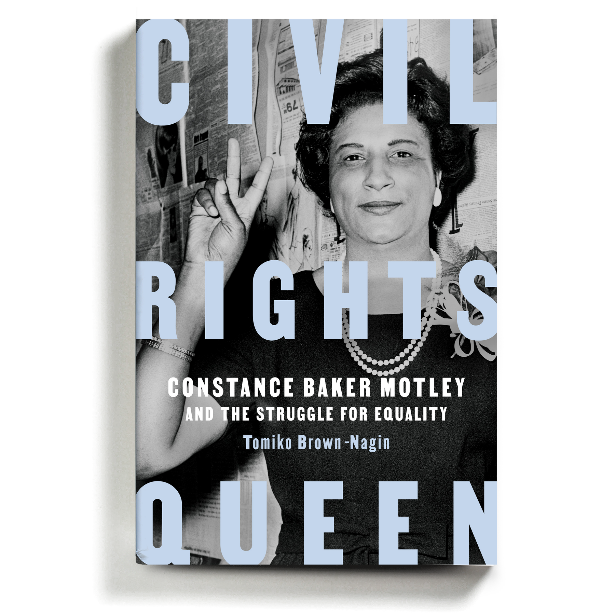

Constance Baker Motley was not only the first Black woman to argue before the Supreme Court (winning an astonishing nine of 10 cases), but she was also the first black woman to be appointed to the federal judiciary – President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed her to the Southern District of New York. In her terrific new book on Motley’s life and legacy – called “Civil Rights Queen: Constance Baker Motley and the Struggle for Equality“- Harvard law professor Tomiko Brown-Nagin Poignantly describes Motley’s life from the time that she was born to a working-class family during the Great Depression, to her role as one of the principal strategists of the Civil Rights Movement and for her legal defense of Martin Luther King Jr., the Freedom Riders, and the Birmingham Children Marchers when she was a civil rights lawyer for the NAACP, to her service in the New York State Senate and as Manhattan Borough President, to her becoming the first Black woman serving in the federal judiciary.

In her terrific new book on Motley’s life and legacy – called “Civil Rights Queen: Constance Baker Motley and the Struggle for Equality“- Harvard law professor Tomiko Brown-Nagin Poignantly describes Motley’s life from the time that she was born to a working-class family during the Great Depression, to her role as one of the principal strategists of the Civil Rights Movement and for her legal defense of Martin Luther King Jr., the Freedom Riders, and the Birmingham Children Marchers when she was a civil rights lawyer for the NAACP, to her service in the New York State Senate and as Manhattan Borough President, to her becoming the first Black woman serving in the federal judiciary.

On November 8, 2016, the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral argument in a case Helmer Friedman LLP successfully convinced the high court to hear. The case — Lightfoot v. Fannie Mae, Cendant Mortgage Corporation case (14-1055) — concerns whether individual homeowners who have been wrongly or fraudulently foreclosed upon by Fannie Mae have the right to sue the mortgage giant in the state courts.

On November 8, 2016, the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral argument in a case Helmer Friedman LLP successfully convinced the high court to hear. The case — Lightfoot v. Fannie Mae, Cendant Mortgage Corporation case (14-1055) — concerns whether individual homeowners who have been wrongly or fraudulently foreclosed upon by Fannie Mae have the right to sue the mortgage giant in the state courts.