Shattered Career Dreams

Navigating Allegations and Accountability in Federal Agencies

The Wall Street Journal recently featured a compelling investigative report by Rebecca Ballhaus, unveiling a troubling culture at the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). The article exposes a toxic work environment marred by strip clubs, lewd photos, and boozy hotel stays.

For years, the FDIC has struggled with a pervasive “boys’ club” culture marked by sexism and frequent sexual harassment. This environment has particularly affected female staff, especially examiners, who have experienced discrimination, missed promotion opportunities, and felt marginalized in a culture that favors male accomplishments. The mishandling of misconduct claims has heightened employee turnover, with inappropriate actions by supervisors and managers fostering a consistently hostile work environment. Rather than address the core issues, the agency often merely transferred perpetrators, a move widely criticized for its ineffectiveness.

“The kind of abuses that were documented in the report are a totally unacceptable way to treat employees at the FDIC and not in line with the core values of the Biden administration,” Yellen told reporters.

Initially optimistic and ambitious new recruits quickly become disenchanted with the workplace, stifled under a glass ceiling maintained by improper conduct and a prevailing boys’ club attitude. Alarming are the claims tied to events led by field supervisor Hien “Jimmy” Nguyen, showcasing the blurred lines and poor judgment that perpetuate this toxic environment. Despite these allegations, Nguyen’s advancement within the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency highlights a disturbing lack of accountability in federal financial regulatory bodies.

Amidst the controversy stands Kevin Burnett, a former senior examiner at the FDIC, who provides a firsthand account of the toxic culture permeating the agency. Burnett’s experience, marked by over a decade of service, reflects a workplace fraught with challenges not just from the nature of the work itself but from a deeply embedded culture of exclusion and impropriety. He recounts instances where professionalism was overshadowed by the personal indulgences of his colleagues, leading to an environment where serious work and meritocracy were often sidelined. His observations shed light on a system struggling to reconcile its esteemed mission with the everyday realities of its internal culture, further complicating the lives of those committed to its success. Secretary Yellen’s condemnation of these practices reveals a deep disconnect between the administration’s declared values and the realities faced by its workforce.

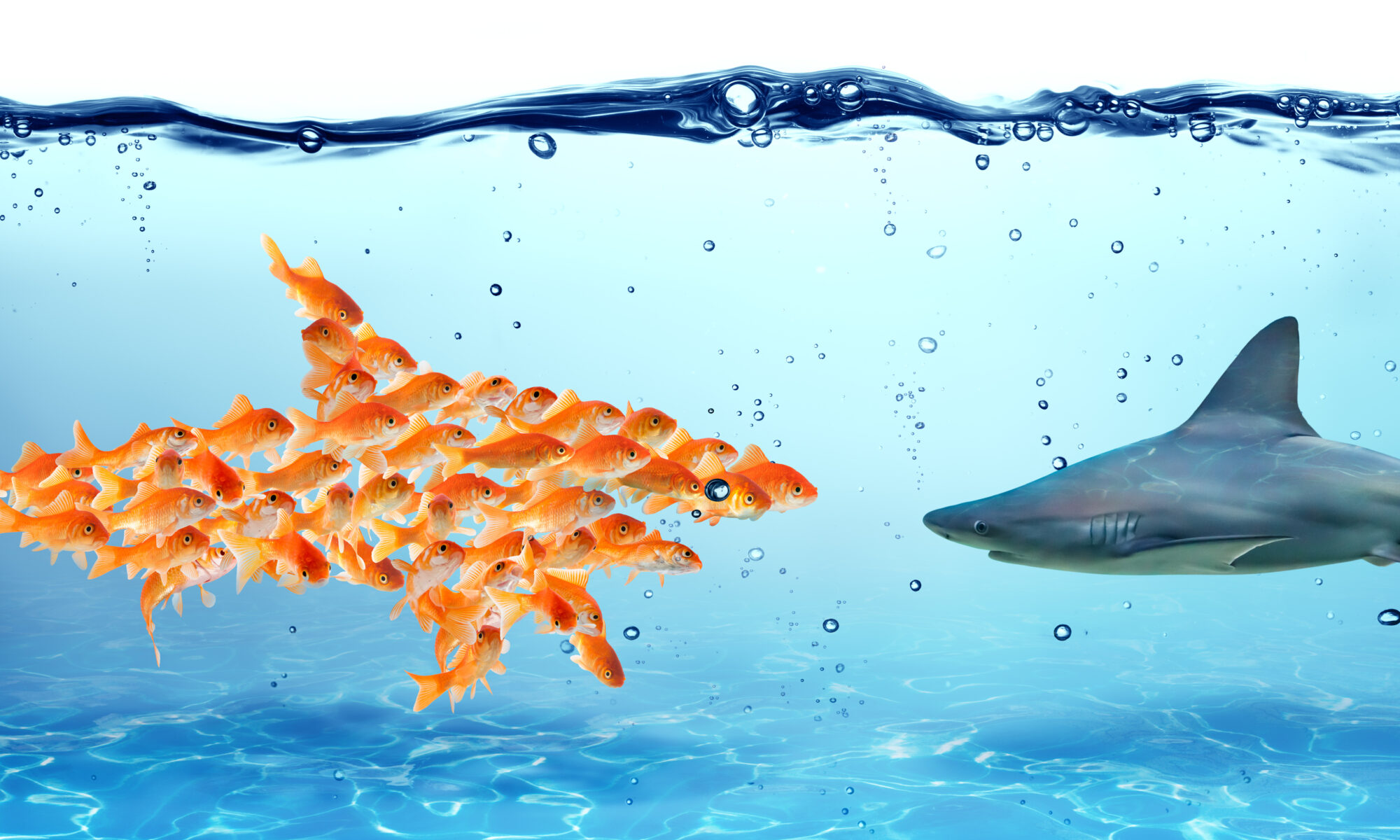

Promising female professionals find themselves sidelined, their potential limited not by their capabilities but by a workplace culture that measures their value by their willingness to submit to a demeaning exchange—success at the expense of personal integrity. This toxic environment spills over into their personal lives, where mandatory social events and excessive drinking blur professional lines. Opportunities to lead projects are dangled and then snatched away, affecting their performance reviews and penalizing them for perceived shortcomings.

Attempts to challenge and change these norms often meet with indifference or retaliation, muffling demands for equitable treatment and sustaining a cycle of inaction. Consequently, the possibilities for career progression are bleak, overshadowed by the toxic dominance of a male-centric workplace. This grim reality forces many talented individuals to exit the FDIC, dismantling their aspirations and underscoring the urgent need for authentic workplace equality. This tale of wasted potential and deferred dreams is a compelling plea for systemic reform.

The FDIC faces severe scrutiny for fostering a work environment steeped in sexual discrimination and harassment, leading to notably high turnover rates, particularly among female examiners who feel marginalized. The tangible impact of this harmful culture extends beyond talent loss. Training a commissioned examiner represents a significant investment, approximately $400,000 over four years. With the resignation rate of examiners-in-training more than doubling recently, the financial strain is considerable, affecting the agency’s fiscal well-being.

Additionally, the FDIC confronts significant financial risks from costly lawsuits over sexual harassment and discrimination allegations. Recent instances of misconduct by supervisors and managers have led to numerous legal actions and complaints, and the agency’s reluctance to implement stringent disciplinary measures has only increased its legal vulnerability.

Beyond the financial costs, the cultural damage is profound. Persistent harassment and discrimination have depleted employee morale, undermining productivity and performance and exacerbating issues like poor mental health among the staff.

In summary, the ongoing culture of sexual discrimination and harassment at the FDIC incurs significant expenses—financially, through increased turnover, legal challenges, and training costs, and intangibly, through lowered morale, hindered employee retention, and a tarnished reputation.

Like this:

Like Loading...