Pita Pit Faces Pregnancy Discrimination Lawsuit

QSR Pita USA Inc., the franchisee behind Pita Pit restaurants, is defending itself against serious allegations of pregnancy discrimination after allegedly firing an employee who requested to work from home due to pregnancy-related nausea. The lawsuit, which targets the company and its affiliates, highlights ongoing workplace challenges faced by pregnant employees nationwide.

The case centers on allegations that management called the employee’s pregnancy a “distraction” before terminating her employment. This incident raises critical questions about employer obligations under federal law and the rights of pregnant workers seeking reasonable accommodations.

Understanding Federal Pregnancy Discrimination Laws

Three key federal laws protect pregnant workers from discrimination and ensure access to necessary accommodations.

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

Title VII, amended by the Pregnancy Discrimination Act, prohibits sex discrimination, including pregnancy-based discrimination. Under this law, employers cannot make employment decisions based on:

- Current pregnancy

- Past pregnancy history

- Potential for future pregnancy

- Medical conditions related to pregnancy or childbirth

- Breastfeeding or lactation needs

The law requires employers to treat pregnant employees the same as other temporarily disabled workers. This means if accommodations are provided for other medical conditions, similar considerations must be extended to pregnancy-related limitations.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)

While pregnancy itself is not classified as a disability under the ADA, pregnancy-related conditions often qualify for ADA protections. These conditions may include:

- Severe morning sickness

- Gestational diabetes

- Pregnancy-related high blood pressure

- Other complications requiring medical intervention

When pregnancy-related conditions constitute a disability, employers must engage in the interactive process to identify reasonable accommodations that allow the employee to perform essential job functions.

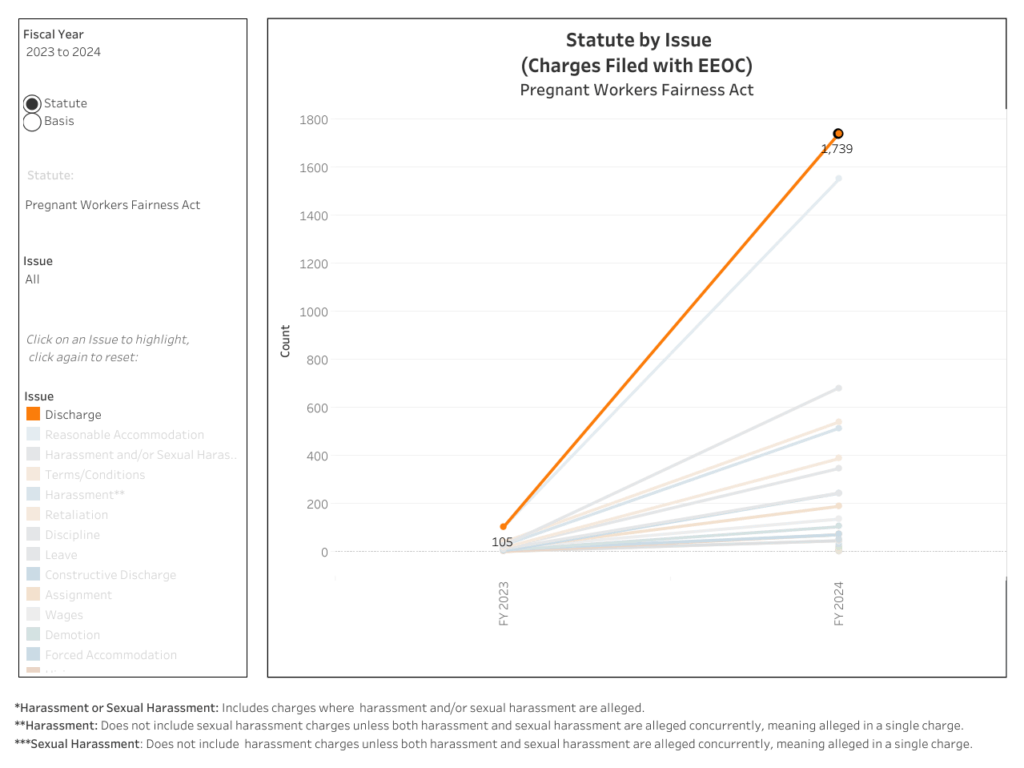

The Pregnant Workers Fairness Act (PWFA)

Enacted in 2023, the PWFA specifically addresses accommodation requests for pregnancy-related limitations. The law requires employers to provide reasonable accommodations unless doing so would cause undue hardship. Significantly, the PWFA prohibits forcing employees onto leave when other feasible accommodations exist.

Details of the Pita Pit Lawsuit

The lawsuit against QSR Pita USA Inc. presents a troubling narrative of alleged pregnancy discrimination that violates multiple federal protections.

The Employee’s Experience

According to court documents, the employee had previously worked from home successfully without receiving negative performance feedback. When pregnancy-related nausea began affecting her ability to work in the office, she requested a reasonable accommodation to continue working remotely.

The request was reportedly denied, and management allegedly characterized her pregnancy as a “distraction.” This language demonstrates the type of stigmatizing attitude that federal laws specifically prohibit.

Legal Violations Alleged

The lawsuit claims violations of both Title VII and the ADA. The allegations suggest that:

- The employer failed to engage in good faith discussions about accommodations

- Management used discriminatory language regarding the employee’s pregnancy

- The termination was based on pregnancy-related limitations rather than job performance

- The company did not treat the employee’s situation consistently with other accommodation requests

Corporate Liability

The lawsuit names not only QSR Pita USA Inc. but also its shareholders and successor company, BubbaMax LLC. This comprehensive approach signals that corporate restructuring cannot shield employers from liability for discriminatory practices.

Legal Implications for Employers

The Pita Pit case illustrates several critical legal risks that employers face when handling pregnancy accommodation requests improperly.

Potential Damages

Pregnancy discrimination lawsuits can result in substantial financial liability, including:

- Back pay and front pay for lost wages and future earning capacity

- Compensatory damages for emotional distress and other non-economic harm

- Punitive damages when discriminatory conduct is particularly egregious

- Attorney fees and court costs in successful cases

- Injunctive relief requiring policy changes and training programs

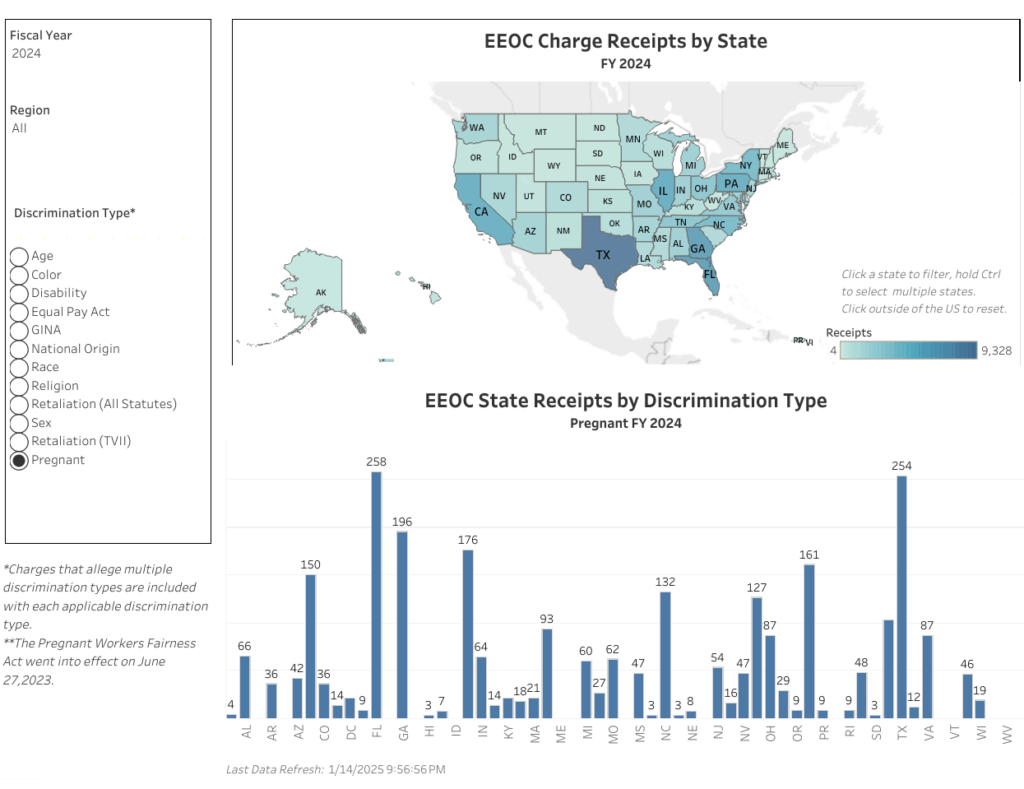

Regulatory Consequences

Beyond civil liability, employers may face investigation by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). The EEOC has broad authority to investigate discrimination claims, require document production, and pursue enforcement actions against non-compliant employers.

Reputational Damage

High-profile discrimination cases can damage an employer’s reputation, affecting recruitment, customer relationships, and business partnerships. The negative publicity associated with pregnancy discrimination allegations can have lasting consequences for brand perception.

Employee Rights Under Federal Law

Pregnant employees possess extensive rights under federal law that protect against discrimination and ensure access to reasonable accommodations.

Accommodation Rights

Under the PWFA, pregnant employees can request accommodations for limitations related to pregnancy, childbirth, or related medical conditions. Common accommodations include:

- Schedule modifications such as flexible start times or break schedules

- Work environment changes like ergonomic equipment or temperature adjustments

- Duty modifications including temporary reassignment of physically demanding tasks

- Remote work arrangements when job duties can be performed from home

- Leave policies that provide time for medical appointments and recovery

Protection from Retaliation

Federal law strictly prohibits retaliation against employees who:

- Request reasonable accommodations

- File discrimination complaints

- Participate in investigations or legal proceedings

- Oppose discriminatory practices

Wrongful termination following an accommodation request, as alleged in the Pita Pit case, constitutes prima facie evidence of retaliation.

Interactive Process Requirements

When an employee requests an accommodation, employers must engage in an interactive process to identify effective solutions. This process requires:

- Good faith participation from both parties

- Timely response to accommodation requests

- Consideration of multiple options rather than automatic rejection

- Documentation of discussions and decisions

- Ongoing evaluation as circumstances change

ADA Accommodations for Pregnancy-Related Conditions

The intersection of pregnancy and disability law creates additional protections for workers experiencing pregnancy-related complications.

Qualifying Conditions

While pregnancy itself is not an ADA disability, related conditions frequently qualify for protection:

- Hyperemesis gravidarum (severe morning sickness)

- Gestational diabetes requiring dietary modifications or medical monitoring

- Pregnancy-induced hypertension necessitating stress reduction or position changes

- Complications requiring bed rest or activity restrictions

- Postpartum depression or anxiety disorders

Accommodation Examples

ADA accommodations for pregnancy-related disabilities might include:

- Modified work schedules to accommodate medical appointments

- Temporary job restructuring to eliminate problematic tasks

- Assistive technology to reduce physical demands

- Environmental modifications such as proper lighting or seating

- Leave as a last resort when other accommodations are insufficient

Undue Hardship Defense

Employers can deny accommodation requests only when they impose undue hardship, considering factors such as:

- Cost of the accommodation relative to the employer’s resources

- Impact on other employees and operations

- Availability of alternative accommodations

- Safety considerations for the employee and others

Preventing Pregnancy Discrimination in the Workplace

The Pita Pit lawsuit serves as a cautionary tale for employers seeking to avoid similar legal challenges.

Policy Development

Comprehensive pregnancy accommodation policies should:

- Clearly outline the interactive process for requesting accommodations

- Provide examples of common accommodations and their implementation

- Establish timelines for responding to and implementing requests

- Prohibit discriminatory language and conduct regarding pregnancy

- Include complaint procedures for reporting discrimination

Manager Training

Supervisors and managers require specific training on:

- Legal requirements under Title VII, ADA, and PWFA

- Appropriate responses to pregnancy announcements and accommodation requests

- Documentation practices for accommodation discussions

- Avoiding discriminatory language and stereotypical assumptions

- Escalation procedures for complex situations

Creating an Inclusive Culture

Beyond legal compliance, employers benefit from fostering inclusive workplace cultures that:

- Celebrate diversity and support working parents

- Provide comprehensive benefits, including adequate parental leave

- Offer flexibility in work arrangements when operationally feasible

- Communicate support for employees during significant life transitions

- Measure and address workplace climate issues through regular assessments

Taking Action Against Pregnancy Discrimination

Employees who experience pregnancy discrimination have multiple avenues for seeking justice and protection.

Filing EEOC Complaints

The EEOC complaint process provides several advantages:

- No cost to file complaints

- Investigation services by experienced federal investigators

- Mediation opportunities for faster resolution

- Right to sue letter enabling private litigation

- Broad remedial authority including monetary damages and injunctive relief

Documentation Strategies

Effective documentation strengthens discrimination claims:

- Written communications about accommodation requests and employer responses

- Medical records supporting the need for accommodations

- Performance evaluations demonstrating job competency

- Witness statements from colleagues who observed discriminatory treatment

- Company policies relevant to accommodation and discrimination issues

Legal Representation

Employment law attorneys provide crucial expertise in:

- Evaluating claim strength and potential damages

- Navigating complex procedures and filing requirements

- Negotiating settlements that fully compensate for harm

- Litigating cases when settlement negotiations fail

- Protecting against retaliation during the legal process

Why Legal Consultation Matters

The complexities of pregnancy discrimination law require professional legal guidance to ensure proper protection of employee rights.

Case Evaluation

Experienced employment attorneys can:

- Assess legal claims under applicable federal and state laws

- Identify all potential defendants, including corporate entities and individuals

- Calculate damage,s including economic losses and emotional harm

- Evaluate settlement prospects and litigation risks

- Develop a litigation strategy tailored to specific circumstances

Statute of Limitations

Federal discrimination laws impose strict time limits for filing complaints:

- EEOC charges must typically be filed within 180 days (extended to 300 days in some jurisdictions)

- Federal lawsuits generally require EEOC right-to-sue letters

- State law claims may have different time limits and procedures

- Documentation preservation becomes critical as time passes

Maximizing Recovery

Professional legal representation often results in:

- Higher settlement amounts through effective negotiation

- Comprehensive damage calculation including all available remedies

- Stronger legal positions through proper case development

- Better outcomes in complex multi-defendant cases

- Protection from retaliation during the legal process

Seeking Justice for Pregnancy Discrimination

The Pita Pit lawsuit underscores the persistent challenges pregnant workers face in securing equal treatment and reasonable accommodations. When employers fail to meet their legal obligations, affected employees have powerful tools for seeking justice and preventing future discrimination.

Federal laws provide robust protections for pregnant workers, but these rights are only meaningful when properly enforced. The alleged conduct in the Pita Pit case—denying reasonable accommodations and using discriminatory language—represents exactly the type of behavior that pregnancy discrimination laws were designed to prevent.